The Seuso treasure is a treasure trove from the late Roman imperial period (4th–5th century). It takes its name from Seuso, the owner of the so-called hunting or Seuso platter, named on the inscription. Its pieces are typical accessories of a ceremonial feast set, including vessels used for cleaning and beautification. Its owner may have hidden it in the last decades of the 4th century or early 5th century, presumably to escape a war conflict. The ensemble as we know it today consists of 14 large silver vessels for eating, cleaning and beautification from the 4th century and a copper cauldron where they were hidden.

This priceless treasure of European textile art was originally intended as a chasuble. According to the hexameter inscription on it, the chasuble was commissioned in 1031 by King Stephen I and Queen Gisela for the Provostry of the Virgin Mary in Székesfehérvár. The masterful gold embroidery covering almost the entire surface was created according to a complex pictorial program, which, according to some researchers, may have been based on the Te Deum or the Litany of All Saints. Its significance is further enhanced by the fact that it was used as the coronation mantle of Hungarian kings until the 20th century.

Stylized bronze waterfowl figurines made by wax casting. Their bodies show ornamentation of plastic ribs and grooves. The back of the unknown find (left) has suspension ears, the head of the other one, from Csicser (right) has horns. The scientific analysis of the bird figurine recovered from Liptovský Hrádok suggests that these objects may have been grease lamps (Csicser and unknown site, 1050–800 BC)

The golden stag, dating to the end of the 7th century BC or the 6th century BC, is one of the most spectacular objects of the Iron Age of the Carpathian Basin, and a representative of the so-called Scythian animal style. Once about 37 cm long, it was made from a hammered gold plate, which was embossed and worked into a relief. The object was found in a burial mound in 1928, along with a gold chain with lion figures, ornamental buttons and a pendant. Similar golden stags have been found in monumental Scythian burial mounds on the northern shores of the Black Sea, and it is possible that the Hungarian example was made by a master craftsman living east of the Carpathians. Observations made during the excavation of the tombs here and the small rings on the back of the plate, which allowed it to be sewn on, suggest that the golden stag may have served as a quiver ornament for its noble owner, buried in the 6th century BC.

The Seuso treasure is a treasure trove from the late Roman imperial period (4th–5th century). It takes its name from Seuso, the owner of the so-called hunting or Seuso platter, named on the inscription. Its pieces are typical accessories of a ceremonial feast set, including vessels used for cleaning and beautification. Its owner may have hidden it in the last decades of the 4th century or early 5th century, presumably to escape a war conflict. The ensemble as we know it today consists of 14 large silver vessels for eating, cleaning and beautification from the 4th century and a copper cauldron where they were hidden. Among the 30 or so precious-metal assemblages known from the late imperial period, including pieces of banquet sets, the Seuso treasure is of outstanding artistic and material value. In terms of total weight, it is the most valuable of the surviving late imperial silver jewellery treasures. The hoard was discovered in the 1970s. Since then it has been through many vicissitudes and has remained hidden from the public for decades. The Hungarian state successfully negotiated the return of the 15 known pieces of the treasure in 2014 and 2017. Thanks to this effort, the general public is now welcome to admire this outstanding artistic collection of the late imperial period. Compared to similar treasure troves and banqueting illustrations, other pieces, including a stand, small tableware, cutlery and glasses, may have been part of the collection. These, if they did exist, are currently lying somewhere hidden. The common feature of the silver vessels is the purity of their material and their ostentatious size and weight, making them among the largest known Roman silver vessels. The total weight of the silver vessels in the hoard is 68.5 kg.

The Roman lantern-shaped brooch, containing a large onyx stone, was worn exclusively by the emperors of the Roman Empire. This first-rate goldsmith work is a rare surviving example of a type of fibula known from reliefs and mosaics. The object, made in a late antique workshop in the 360–370s, is thought to have belonged to the royal family of the Goths and was found in a treasure trove buried in Szilágysomlyó in the mid-5th century.

Szilágysomlyó, First half of the 5th century CE. (Hungarian National Museum, Between East and West, Room 7)

From one of the most important Hun period treasure troves of the Carpathian Basin, this late antique pure gold masterpiece was made in the last third of the 4th century. Worn by the Germanic elite, it is a rare reminder of the fashion for an outer female garment with a pair of fibulae on the shoulder. Decorated with embossed lion shapes, rock crystal, garnet stone and glass inlays, it is a much-used, worn piece of jewellery.

The palmette motif of the Galgóc sabretache plate, woven into an endless net, is reminiscent of oriental textiles or frescoes in Sogdian cities. The Hungarians were introduced to this pattern in their eastern settlements. A man's grave unearthed in 1868 is recorded to have contained horse bones, a choker, a pair of earrings and an Arabic silver dirham. The pierced coin was minted by the emir of Samarkand Nasribn Ahmed (914–943), issued in Samarkand in 918–919, and its last owner may have worn it sewn onto his clothes or harness at the end of the first third of the 10th century.

Conical cap top decorated with gilded silver palmettes. Its surface is interlaced with vines, interspersed with triple leaf clusters, and finished with a ribbon braid.

The Byzantine, gilded silver holy water font inscribed in Greek is supported by three – partially reconstructed – lion and griffin ornamented legs, its body a hexagonal form, the wider base is connected to the narrower upper part by a stepped, sloping section. Its movable upper handle is joined to the vessel at the bust of two youths, and above, at the level of the youths' busts, is the corrupted Greek inscription, the current interpretation of which is: "Christ, the living fountain of healings". The palmette vines covering the vessel are set against a circular punched background, with three palmettes alternating with three mythological beasts in the lower almond-shaped space of the vines. The palmettes are an early example of the so-called flower-leaf ornamentation renewed at the Byzantine imperial court in the mid-10th century, based on Chinese designs.

The seven semi-circular gold plates of the Byzantine cloisonné ensemble, discovered in 1861 in Nyitraivánka (today: Ivanka pri Nitre, Slovakia), depict the "Roman" Emperor Monomachus IX Constantine (r. 1042–1055) and six standing female figures, while two medallions show the bust of apostolic brothers, Saint Andrew and Saint Peter. The plates decreasing in size in pairs, depict female figures, the last descendants of the Macedonian dynasty, Zoë (d. 1050) and her sister, the Empress Theodora (d. 1056), two dancing women and two figures of the Virtues, Truth and Humility, surrounded by a vine scroll of birds and a pair of cypresses (the Virtues) respectively. The plates may originally have been mounted on a cap and their universal peace programme could be interpreted in a Sasanid, Islamic, ancient and Old Testament context, while the two apostles, which were included in this ensemble for secondary use, referred to Rome and Constantinople, the scene of their activities, and the Latin and Greek churches they led respectively.

The gilded silver buckle found at Bajna was made in the mid-13th century using the opus duplex technique particularly popular at the courts of Andrew II and Béla IV.

The lily and rosette ornamented crown was found in 1838 in a royal tomb of a Dominican monastery on Margaret Island – perhaps the tomb of King Stephen V. It may have been crafted in the second half of the 13th century, influenced by French classical Gothic style.

The centaur and the flute-playing boy figure on his back (probably Chiron and Achilles) are the product of the famous Hildesheim bronze foundry from the 1220s, and may have come to Hungary thanks to the close links established with the German Empire at the court of Andrew II.

Late 14th century/early 15th century

(History of Hungary, Part One, Room 2)

Many of the carvings on the ceremonial saddle bought by Miklós Jankovich in Bucharest feature popular courtly themes around the scene of Saint George and the dragon, but also the badge of the Order of the Dragon, founded by King Sigismund is visible, which may support the legend that it was originally owned by Vlad Tepes, better known as Dracula, who got his name because of his membership in the Order.

From the early 1500s, the pair of cruets from Nagyvárad (today: Oradea, Romania) combines late Gothic naturalism with filigree decoration. Purchased from the Bethlen family, this pair of cruets, crafted in the first quarter of the 1500s, came from the cathedral of Nagyvárad according to family tradition, combines late Gothic naturalistic pear-shaped decoration from Nuremberg with more abstract filigree surface decoration, considered characteristically Hungarian. One of the earliest known drawings of a pear-shaped figurine is by Albrecht Dürer, whose father was from Ajtós near Nagyvárad, and the object may thus bear witness to the Nuremberg-Hungarian relations among gold- and silversmiths that existed in Dürer's time.

The late 15th-century chalice, with its fully aniconic, beaded, foliate scroll decoration, was commissioned by János Ernuszt, Master of the Horse of King Ulászló I, later ban of Croatia and Slavonia (1507–1510). It bears the coat of arms of his father-in-law and mother-in-law, Imre Pálóczi, Master of the Horse, and Dorottya Rozgonyi. János Ernuszt's wife, Anna Pálóczi, died in 1494, so the chalice must have been commissioned before then.

The late 17th-century inscription on the goblet's base links it to King Matthias, although its specific technique (vetro a retortoli) was patented in Murano only in 1527. The goblet survives as a legacy of the Batthyány family, because members of the family held the office of Lord High Cupbearer to Louis II and later the Habsburgs, so it is assumed that the magnificent piece originated in Habsburg use and was later reinterpreted as part of the 17th-century cult of Matthias.

The silk tapestry was crafted before 1476, probably in the workshop of Francesco Malocchi, the most famous Florentine weaver of the 15th century, designed by Antonio Pollaiuolo. It shows the coat of arms of King Matthias and his countries (Hungary, Dalmatia, Bohemia) in a rich Renaissance ornamental composition. The coat of arms of Matthias was later overlaid with his own by Tamás Bakócz, Archbishop of Esztergom.

The sword, with its ornate scabbard decorated with the papal and della Rovere family coat of arms, was a gift from Pope Julius II, presented to King Ulászló II by the Pope's envoys at the Diet of Tata in 1510, as an urge to set out on a campaign against the Turks.

Although precious opal was a popular gemstone in early modern jewellery, very few surviving examples are known. This unique piece came to the National Museum with the collection of Miklós Jankovich. Legend has it that the pendant was once Isabella Jagiellon, wife of János Szapolyai's jewel. However, this is not supported by sources and the style of the object contradicts it. However, the beautiful jewel was probably made in Transylvania or Poland in the early 17th century.

The rapid spread of the Renaissance style in Hungary was mainly brought about the splendour of King Matthias's and Queen Beatrix's royal court. An outstanding example of this is the choir stalls commissioned by the Báthori family. The cornices, friezes, dividing and supporting balustrades, back walls, elbow and seat frames, side walls, partitions and linings under the seats were carved and inlaid with Renaissance-style decoration. A full panel shows the names and ranks of the patrons and the year of manufacture (György, István and András Báthori, 1511), while another backrest bears the maker's mark F. Marone. Some of the inlaid backrests depict cabinets with half-open doors and shelves with books and kitchen utensils.

The estates of Lower Austria once paid homage to Miklós Pálffy, one of the commanders of the Christian troops who recaptured Győr from the Turks, with this gold goblet of considerable weight. This important victory is commemorated by the inscription on the shield of the Roman warrior trampling on the Turkish shield: GOT DIE ER 1598 (God's is the glory). The trophy had an adventurous journey in the 17th century, and from 1653 it became the inalienable heritage of the family by the will of Palatine Pál Pálffy. It came into the collection of the National Museum as a donation from the family in the 20th century.

The rosette-shaped pendant is dominated by faceted cut diamonds. The single set or row of gemstones were fastened with delicate, intricate pins and screws on the stylized leaf-shaped, cast "pea-pod" gold frame. The diamonds were probably polished in Antwerp, and the closest parallels to the large pendant can be found in Flemish portrait painting. The unique jewel came to the National Museum with the collection of Miklós Jankovich.

This exceptional goldsmith's object was commissioned by the Transylvanian prince György I Rákóczi for the former monastery, or as we know it today, the Reformed church congregation in Farkas utca, Kolozsvár (today: Cluj-Napoca, Romania). The chalice is special not only because of its rich iconographic programme, but also because it is one of the special relics of princely representation.

According to tradition, Catherine of Brandenburg, the second wife of the Transylvanian prince Gábor Bethlen Gábor, wore this plum-toned silk dress. The garment, consisting of a skirt and bodice, is richly embroidered with metal threads. Tulips, carnations and daisies arranged under arches are motifs frequently used in 17th-century embroidery surviving in Hungarian areas.

Gemstone-decorated emblem of the Royal Hungarian Order of St. Stephen worn by Maria Theresa, 1764

(History of Hungary, Part Two, Room 10)

According to tradition, a Hungarian-style coat, dolman, trousers and cap, made of light blue floral-printed rip silk, was prepared for Maria Theresa's first-born son Joseph. There are also several depictions of the monarch and her children in Hungarian-style clothing.

Johann Andreas Stein's simple little travelling instrument, built in 1762, is not just the only surviving clavichord of the famous Augsburg organ builder (the most notable of his innovations is the so-called Viennese-style mechanism), but also the portable instrument of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. The clavichord and all its documents were acquired by the museum in 1965.

Count István Széchenyi, initiator of the Hungarian reform movement, donated one year's income of his estates to the Hungarian Academy of Sciences at the 1825 Diet. His many impressive achievments served the creating of modern Hungary. He founded a casino (club) to discuss political, economic and social issues. In his works (Credit, World, Stage), he outlined the first comprehensive programme for the rise from feudal misery to bourgeois conditions. The high point of his numerous reform initiatives was the construction of a permanent bridge, the Chain Bridge, linking Pest and Buda, and upturning economic activity and transport so that the medieval towns on both banks of the Danube could be transformed into one major city, a true Hungarian capital, which could rival Vienna in attracting the royal centre of the entire Habsburg Empire to the banks of the Hungarian Danube.

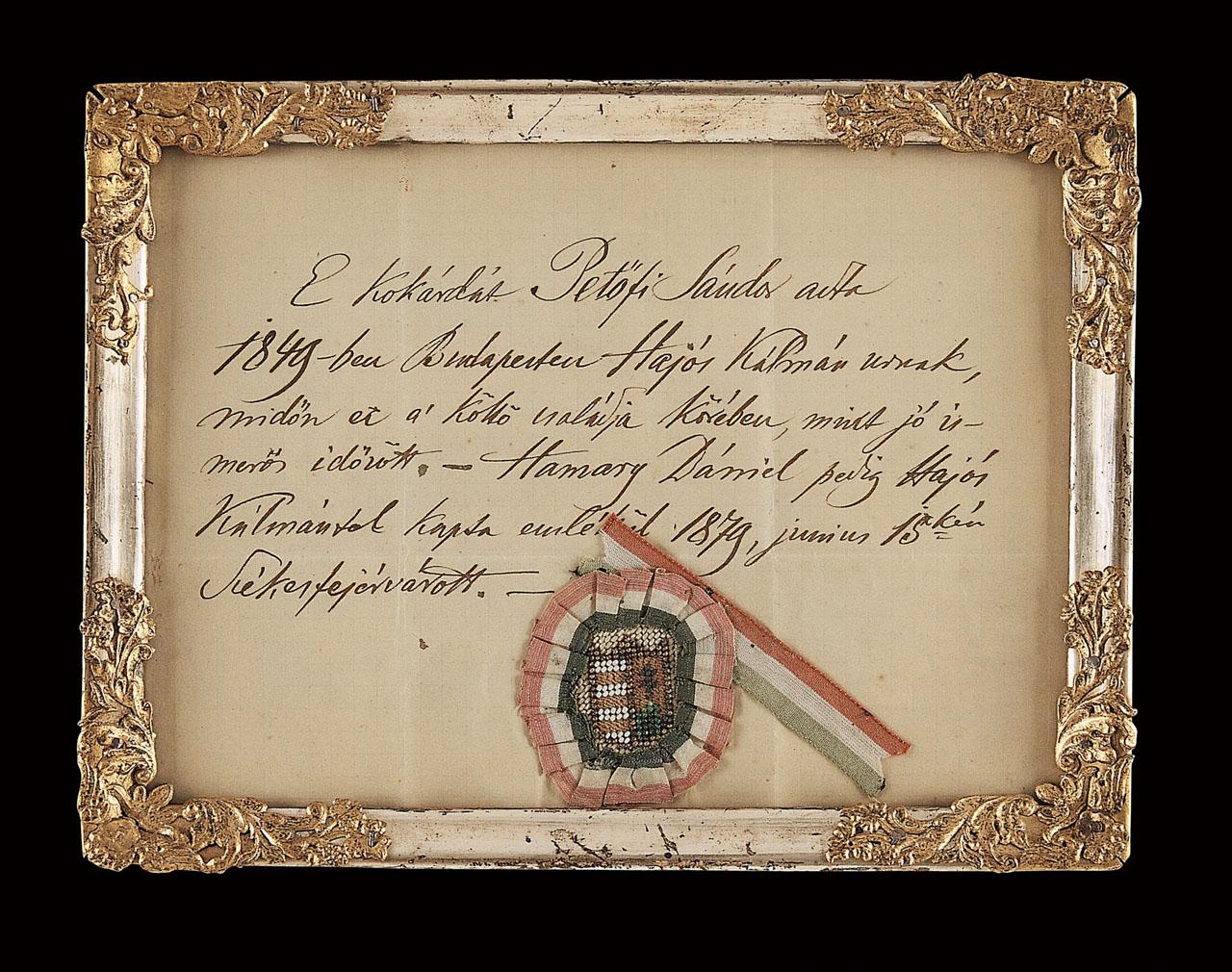

Sándor Petőfi poet is one of the most significant and influential figures in the history of Hungarian literature.

As one of the leaders of the March youths who sparked off the revolution of March 15, 1848, and later as a martyr of the 1848–49 War of Independence, he became one of the central legendary figures of national heroic tradition. His life became as much of a cult as his poetry. The national cockade shown here, according to the authenticating document, belonged to Sándor Petőfi.

Artur Görgei's 1845 M cavalry officer's sabre, with a magnifying glass in the hilt, with which the general – famous for his short sightedness – read maps. On the double-edged blade there is an inscription "For Homeland, Freedom and King", as well as the Hungarian coat of arms, and the date "15 March 1848" and war trophies. The length of the sabre is 101.5 cm.

White piqué vest with bullet holes worn by Count Lajos Batthyány at his execution. The Prime Minister of the first accountable Hungarian government was orderd to be executed in the courtyard of the New Building in Pest on 6 October 1849 by Haynau, the Austrian military commander who had been given full military authority after the defeat of the 1848-49 War of Independence. On her last visit to the death row, Countess Antonia Zichy, Batthyány's faithful wife, smuggled in a small sharp dagger for her husband, with which Batthyány attempted suicide the night before his execution to avoid the humiliation of hanging. The life-threatening wound on his neck eventually changed his sentence to execution by a firing squad. The vest he was wearing at the time of his execution was donated to the Hungarian National Museum by his widow.

The costume of braided broadcloth "atilla" jacket and straight red trousers was once worn by Lajos Kossuth Governor-President. It was donated to the Hungarian National Museum by his son's widow, Mrs. Ferenc Kossuth.

In 1873, after the celebrations of the 50th anniversary of his artistic career, Ferenc Liszt decided to donate his most treasured objects to the National Museum, in a manner befitting a patriot. The most notable object of the Liszt legacy is the piano that Liszt acquired in 1846, and which he himself treated as a relic: the instrument Thomas Broadwood sent to Beethoven to Vienna in 1817.

Made of blue velvet with embroidered silver threads, this gown with train was made for the coronation of Franz Joseph I and Queen Elizabeth. Later, after minor alterations, it was worn by Gabriella Széchényi at the coronation of Charles IV in 1916.

Interior of Ferenc Deák's room in the historical exhibition.

Adler workshop, 1896

This large pipe, made in the renowned workshop of Fülöp Adler and Son, sums up the way Hungary’s history was seen at the time of Hungary’s Millennial Celebrations in 1896, one thousand years after the arrival of the Hungarians in the Carpathian Basin. Carved from meerschaum, the bowl of the pipe consists of the allegorical female figure Hungaria; she holds the coat of arms of Hungary with its double cross and Árpád stripes. On the long neck part can be seen, on horseback, the conquering tribal chiefs and the proud figure of Árpád, the ruling prince. On either side of the shank we see the Hungarian people arriving in their new homeland (a farmer leading oxen, people on horseback); these scenes were inspired by the Feszty cyclorama. On the foot part is a half-length portrait of of St. Stephen, the founder of the Hungarian state. On the front side, in pride of place, there is a portrait of King Francis Joseph of Hungary and his consort Queen Elizabeth. Above their heads, two cherubs hold the Holy Crown of Hungary. Like this pipe, the rhetoric of the millennial celebrations extolled Francis Joseph as a second Árpád who, with ‘St. Stephen’s Crown’ upon his head, was launching the Hungarians into the second thousand-year period in their history.

(History of Hungary, Part Two, Room 14)

Princess Elisabeth of Wittelsbach (1837-1898) of Bavaria (family nickname Sisi), wife of Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria was Queen of Hungary from 1867. After the sad years of reprisals following the crushing of the Hungarian War of Independence in 1848/49, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, established by the Compromise of 1867, finally brought reconciliation and a peaceful, prosperous era for both nations. In the run-up to the reconciliation, the Hungarians attached great importance to the young and charming Empress, who was, therefore, held in special esteem by the Hungarian people. The affection was mutual. Princess Elisabeth of Bavaria also had a special sympathy for the Hungarians. Although the dutiful Franz Joseph and Elisabeth had very different personalities, Franz Joseph adored his wife and was deeply devastated by the news of her murder. On the 10th of September 1898, the Queen was in Geneva with a small entourage. After a morning of shopping in good spirits, she was hurrying to the boat station on the promenade along the shores of Lake Geneva with her lady-in-waiting, the Hungarian Countess Irma Sztáray, when the Italian anarchist Luigi Lucheni stabbed her with a sharpened file. After what was thought to be an attempted robbery, Elisabeth was helped off the ground by her lady-in-waiting and passers-by, and continued on her way before reaching the departing boat. However, the queen was taken ill on board and her attendants only discovered her fatal wound when her very tight corset was loosened. She was taken back to her hotel suite as quickly as possible, but the doctors arriving on the spot could only pronounce death.

In the midst of the war, at the end of 1916, the aged ruler of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, Emperor Franz Joseph, died. His successor, the last Hungarian king, Charles IV, was crowned in pre-war ceremonies. The country, along with its good wishes, presented its new ruler with this silver chest.

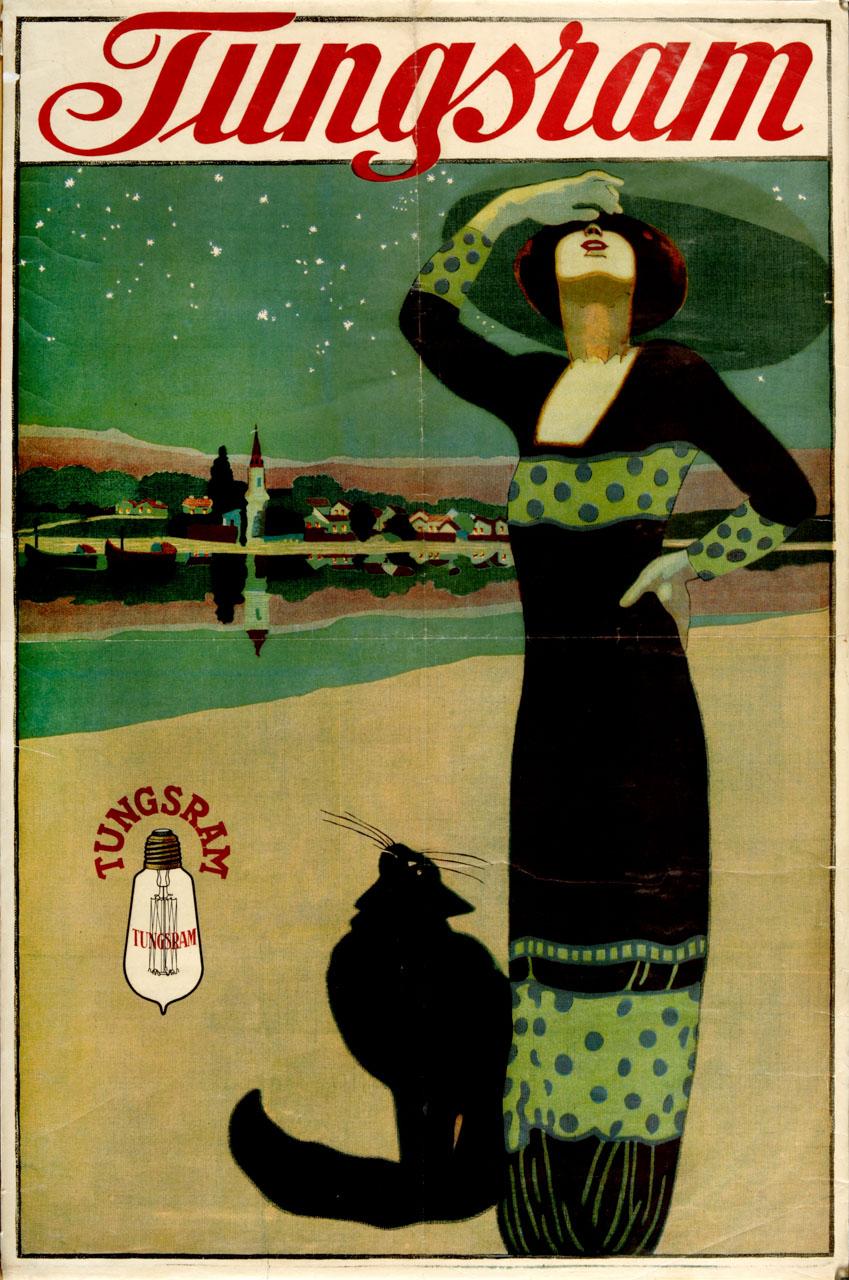

Géza Faragó

Advertisement for incandescent lightbulbs that were made by the Tungsram Factory, cca. 1912

(History of Hungary, Part Two, Room 16)

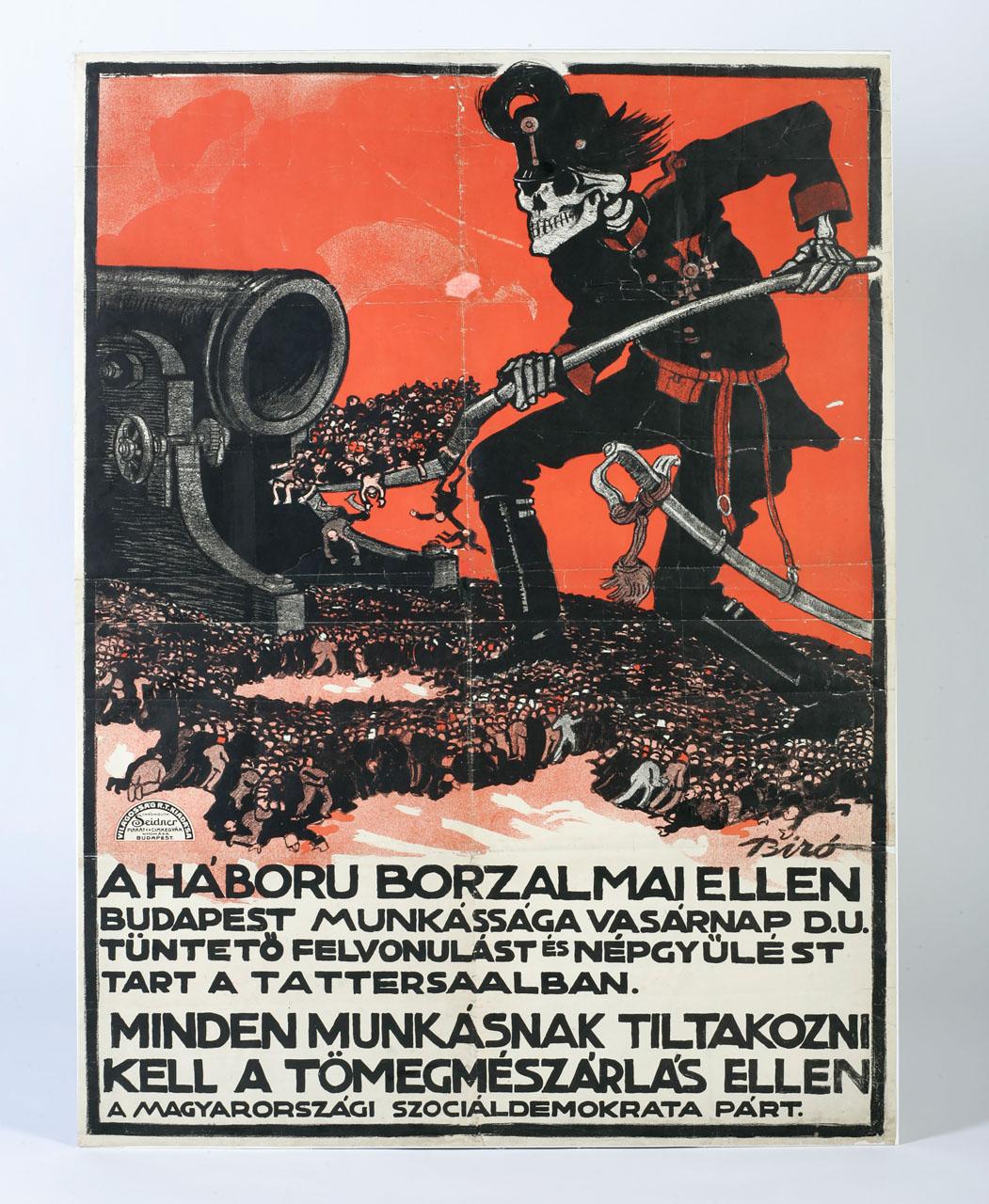

The "Belle Époque" period, the happy times of peace ended with the outbreak of World War I. In Mihály Bíró's iconic poster commissioned by the Social Democratic Party, created in the aftermath of the Balkan Wars (1912–1913), death is shovelling people into the cannon barrel to make cannon fodder.

The Red Locomotive is an emblematic work of the Hungarian avant-garde, evoking both the technical achievements of the Industrial Revolution and the dynamism of the modern world. The red colour of the stylized, highly geometric forms of the locomotive leaves no doubt about the socialist ideals that inspired the painting.

Miklós Horthy, the last commander of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy's navy became the regent of truncated Hungary. Horthy also preferred to wear his naval uniform even as regent. He carried it with him when he was arrested by the Germans occupying Hungary at the end of World War II. The uniform on display was brought back to Hungary from Horthy's emigration in Portugal.

A counterpoint to the Neo-baroque-style: a reading corner in a modern, metropolitan apartment of intellectuals.

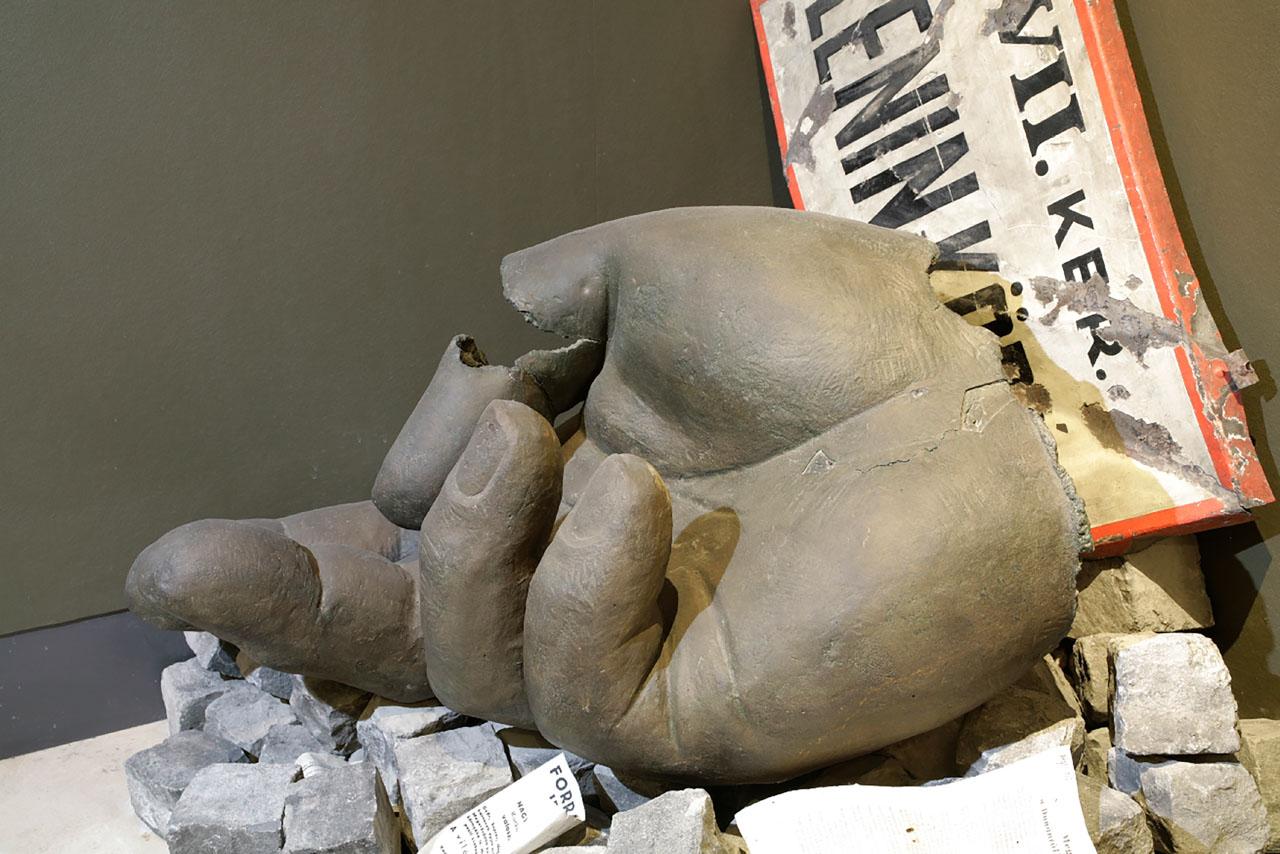

The statue of Stalin (by Sándor Mikus) in the City Park was toppled in the evening of 23 October, the first day of the 1956 revolution. The statue was a prominent symbol of the overthrown regime, and was torn apart by popular anger. Our exhibition presents the "omnipotent" hand.

Table lighter with the initials of the martyr Imre Nagy, prime minister of Hungary during the Revolution of 1956, 1950s

(History of Hungary, Part Two, Room 20)

The fountain pen belonged to József Antall, Prime Minister of the first democratic Hungarian government after the political transition (1990) The pen, placed in a wooden box with the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Spain, is black with gold decoration and a gold-iridium barrel, and was given as a gift to József Antall by Spanish Prime Minister Felipe Gonzales in 1991. The cap of the pen also bears the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Spain.