We would like to inform our esteemed visitors that from 2 December 2025, the exhibition spaces of The Coronation Mantle, The Seuso treasure – The Splendour of Roman Pannonia, the Széchényi Hall, and the Open Repository will be temporarily closed due to renovation works. The expected reopening date of the exhibitions is spring 2026.

Thank you for your understanding. We wish you a pleasant visit to our open exhibitions!

The Seuso Treasure - The Light of Pannonia exhibition features three elegant spaces where visitors can admire one of the most valuable artefacts of the late Roman imperial period. The imposing museum halls highlight the unique artistic value of the Seuso Treasure, while the renewed curatorial concept helps 21st century visitors to decode the message of the treasure's silver vessels. The exhibition's wider material draws attention to the imperial and Pannonian context of the treasure, conveying the mentality, aristocratic lifestyle and self-image of the elite of the late Roman Empire and also the process how the imperial elite of the time converted to Christianity.

Seuso website

Composition of the exhibition

The first room of the exhibition prepares the visitor to understand and appreciate the Seuso treasure by presenting the elite culture of the late Roman Empire and providing the necessary basic information. Here, delving into eight themes and a number of luxury objects from Pannonian sites visitors can learn about the Romans' relationship to silver objects and the prominent role of treasures in society.

The hall, once a corridor, serves as a kind of initiation: from here, visitors enter the two larger rooms where they can see the 14 silver vessels and the copper cauldron used to hide them, as well as the silver stand of Kőszárhegy related to the Seuso treasure.

Curators have placed many of the objects in separate showcases, indicating that the Seuso treasure is not a homogeneous group of objects. Its silver vessels are separate works of art, created in different concepts at different times. Another advantage of this arrangement is that all the showcases can be walked around, and the vessels can be viewed from all sides. Chronological aspects have also been taken into account: the first room contains the earliest pieces of the treasure featuring the Hellenistic artistic tradition best and clearest, while the second room contains the later silver vessels.

In addition to establishing the possible chronological order of the vessels, the exhibition attempts to answer the question of how the decorative repertoire of the artefacts fitted into the visual world of the aristocratic culture of the period and how this expressed the identity of the late Roman imperial elite. It also provides a scholarly reflection on the questions that visitors and the media are keen to address: what are the grounds for claiming that the Seuso treasure is among the most outstanding of treasure troves, both as treasures and in terms of artistic quality? Who was Seuso? How is the silver stand of Kőszárhegy related to the Seuso treasure?

The message of the exhibition, however, focuses not only on the treasure trove and the objects that make it up, but also on the circumstances of its concealment and the story of its discovery. Visitors embark on a journey in the exhibition halls that reveals, through the silver luxury objects on display, both the high culture of the late imperial elite and its destruction. The explorer's journey is also supported by 3D graphics and multimedia content showing films. Touch screens offer the opportunity to playfully explore the details of the objects that can be rotated virtually and to learn more about the objects (e.g. Greek mythological stories depicted on the vessels, the function of the vessels, missing and invisible parts).

The album available in the National Museum's shop serves a similar goal: it supplements the information on display and in the exhibition with unique photographs of artefacts, maps, illustrations and texts by the curators. The Seuso Treasure. The Light of Pannonia is not an exhibition catalogue in the strict sense, it does not follow the exact structure of the exhibition, but reflects on it in many ways: it presents the most significant surviving late Roman silver treasure trove by placing it into the cultural milieu of the late Roman elite and the most glorious luxury objects found in Pannonia.

The creators of the exhibition

The exhibition was directed by Marianna Dági (Museum of Fine Arts), Zsolt Mráv (Hungarian National Museum)

Professional lecturer: László Török (Hungarian Academy of Sciences)

Numismatic expert: András Dabasi, Judit Kardos (Hungarian National Museum)

Graphic design by Anna Farkas (Anagraphic)

Exhibition design by Narmer Architecture Studio, KÖZTI (Középülettervező) Zrt.

Engineering designers. Project management: Merényi Ágnes

English text by Bob Dent, Katalin Rácz

Art conservation by Balázs Lencz, Péter Földessy

Restoration by Krisztina Dúzs, Balázs Lencz, Balázs Lukács, Melinda Nagy, Norbert Németh

Security by János Pataki

Technical management by Tibor Frankovics, Károly Bernáth

Contractors., CLH Hűtés- és Klímatechnikai Kft., Lisys-Projekt Kft. (lighting technology), SAUTER Épület Automatikai és Rendszertechnikai Kft., B Consulting Kft. (safety technology), Beige Bau Kft., HUMAN CONSTRUCT Tervező és Szaktanácsadó Kft.

Vitrine equipment: Andrea Bak, Ákos Marosfalvi, Gyula Miklovics

Professional assistant: Tamás Szabadváry

Museum pedagogy: Zsófia Kenesei, Eszter Suba, Liliána Vattay, Dóra Biricz

Museum pedagogy.

Objects of the Seuso treasure

The Seuso treasure is a treasure trove from the late Roman imperial period (4th–5th century). It takes its name from Seuso, the owner of the so-called hunting or Seuso platter, named on the inscription. Its pieces are typical accessories of a ceremonial feast set, including vessels used for cleaning and beautification. Its owner may have hidden it in the last decades of the 4th century or early 5th century, presumably to escape a war conflict. The ensemble as we know it today consists of 14 large silver vessels for eating, cleaning and beautification from the 4th century and a copper cauldron where they were hidden. Among the 30 or so precious-metal assemblages known from the late imperial period, including pieces of banquet sets, the Seuso treasure is of outstanding artistic and material value. In terms of total weight, it is the most valuable of the surviving late imperial silver jewellery treasures. The hoard was discovered in the 1970s. Since then it has been through many vicissitudes and has remained hidden from the public for decades. The Hungarian state successfully negotiated the return of the 15 known pieces of the treasure in 2014 and 2017. Thanks to this effort, the general public is now welcome to admire this outstanding artistic collection of the late imperial period. Compared to similar treasure troves and banqueting illustrations, other pieces, including a stand, small tableware, cutlery and glasses, may have been part of the collection. These, if they did exist, are currently lying somewhere hidden. The common feature of the silver vessels is the purity of their material and their ostentatious size and weight, making them among the largest known Roman silver vessels. The total weight of the silver vessels in the hoard is 68.5 kg.

The treasure is special because of its namesake, its decoration and the genre scene it depicts. The rim of the platter depicts shows a hunting scene in a wildlife park, featuring exotic animals (antelope, leopard, onager, lion, gazelle). The hunting party returns to the lord's country residence laden with loot. The central medallion is circumscribed by a personalised address in verse commissioned by the donor. The occasion for presenting the gift was a family event, perhaps a wedding. The inscription begins and ends with the Greek letters chi and rho, which are the initials of Christ's name, but could also be interpreted as a sign of victory. The medallion is decorated with scenes from the lives of landowners. Composed around the centre of the platter, in a semi-circular arrangement is a group of people feasting: in the middle, perhaps Seuso and his wife, surrounded by three male guests or family members. In front of them on the table are fish. Two servants offer them food and drink, while others process the game taken at the hunt. A shading tarpaulin is stretched over the head of the hunting party between two trees. The banquet site is the bank of a river rich in fish. The picture is accompanied by an inscription band with the Latin name of Lake Balaton: Pelso. Seuso's favourite horse is also named on the plate: In(n)ocentius. The name, which means 'innocent', could have been given to the animal because of its gentleness or, on the contrary, its wildness. It was also the name given to one of the bloodthirsty bears of Emperor Valentinian I, trained to kill.

The central medallion is framed by a personalised poetic inscription in Latin, engraved on the platter by the commissioner. "HEC SEVSO TIBI DVRENT PER SAECVLA MVLTA POSTERIS VT PROSINT VASCVLA DIGNA TVIS" meaning "May these, O Seuso, yours for many ages be, small vessels fit to serve your offspring worthily!" This suggests a close, intimate relationship between the giver and the recipient. The mention of descendants suggests that the gift may have been presented on the occasion of a significant family event, perhaps Seuso's engagement or wedding. This is supported by the female figure depicted in the hunting party. The inscription begins and ends with the Greek letters chi and rho, which are the initials of Christ's name, set in a wreath and linked together.

There is a depiction of Lake Balaton named PELSO in the Seuso platter's medallion. Pelso is a geographical name in Pannonia: the name of a lake which, according to written sources from the imperial period, can only be identified with Lake Balaton. Pelso was situated in the late Roman province of Veleria, which includes East Transdanubia and the Balaton highlands, which corresponds to the geographical location of Lake Balaton. The lake and its surroundings were popular among the elite of the late Roman provinces for its Mediterranean climate and its magnificent view. The depiction of the platter shows that Seuso's estate may have stretched as far as Lake Balaton with its fish providing ample source of food, and the spectacular view may have made the then owner of the estate proud. For the donor of the Seuso platter was probably familiar with this close emotional attachment.

The silversmith has decorated the geometric platter only on the rim and in the centre. Its concave surface, polished to a glossy sheen, scatters light like a distorted mirror. The edge of the rim is decorated with rhythmically repeating spherical and spindle-shaped beads. The geometric wallpaper pattern of the medallion, surrounded by a gold band and a running dog motif, is composed of interlocking octagonal and rectangular fields filled with stylised rosettes and palmettes. The ornamentation of the platter is based on the shimmer of the silver and gilded surfaces, the matt black of the niello inlays and their playful contrast. At feasts, such large-diameter and heavy platters were used to serve various dishes.

The reliefs that cover the entire surface of the smallest ewer in the Seuso treasure depict Dionysus and his merry entourage. The figures follow one another on each of the eight sides of the ewer and come together in a festive procession. The deity contemplates with satisfaction his enthralled followers and their wild revelry. The Dionysian motifs and scenes, in addition to evoking the deity himself, became, by late antiquity, allegorical representations of happiness and pleasures of friendship, feasting and mundane existence.

The silver casket with a cylindrical body and lid, based on its representations and its former contents, was probably used by the mistress of the family for her daily bathing and beauty treatments. The figurative frieze running around the body of the vessel is divided into two scenes, separated by a curtain, each depicting an episode of evening or morning bathing. In the shorter, erotic scene, we are given a glimpse into the intimate world of a private bathhouse of the period. The longer scene centres on the already dressed mistress, to whom her maids bring a variety of beauty accessories, including a mirror, a jewellery box, a dressing case and an object very similar to the toilet casket. The composition was inspired by the well-known scenes of Aphrodite and the bathing of the three Graces.

Scenes from the story of Hippolytus and Phaedra are shown on the Hippolytus ewer only in the central band, adapted to the shape of the vessel. This is framed by a frieze of boar and lion hunting on the top and a depiction of centaurs hunting animals on the bottom. The handles of the ewer are also richly decorated, with a female mask at the bottom covering the attachment to the body of the vessel, an oak branch covered with acorns along its entire length and goat's heads around the rim. A delicately sculpted, gilded lion figure in solid silver stands as a finger rest at the top of the handle. Acanthus leaves are engraved on the base, and the lid is hinged to open. Traces of gilding are clearly visible on the ewer.

The entire surface of Hippolytus situla, used for carrying water, is decorated with scenes from the story of Hippolytus and Phaedra. Both vessels stand on three legs in the shape of griffins, with male busts on their handles. The bodies of the situlae show traces of gilding.

One of the depictions on the Hippolytus situla B refers to the death of Hippolytus. The young man's horse rears up near a curved tree and a pillar. Pausanias, travelling in Greece in the 2nd century, heard the following story: near Athens, by the temple of Artemis, Hippolytus' horse shied and the youth entangled himself in the bridle, which got caught in a nearby crooked tree, thus hanging himself on it.

The central figure in the relief decoration of the gilded silver amphora is Dionysus, who appears in two different guises. In the prime of his life, as a wreathed youth leaning on his pinecone-tipped staff, he pours wine into the mouth of a panther sitting meekly at his feet. On the opposite page, he is seen as a child riding a giant goat, his staff in hand, his nurse following behind him with a watchful eye. Between them are familiar figures of the god's entourage, who may also refer to a moment in the festivities of Dionysus. The festive merriment, the activities, music, dancing and merrymaking that are so dear to Dionysus are evoked by the bacchantes and Silenus, dancing and playing the drums, cymbals, cymbals and aulos. All of them – surrendering to the power of Dionysus – form a single, rapturous merry-making procession.

The largest piece in the Seuso treasure is the Achilles platter, decorated with scenes from the life of the most famous and distinguished hero of the Trojan War. The wide rim, below the medallion, depicts the birth of Achilles, attended by the gods Zeus, Apollo, Helios, Hermes and Poseidon, as well as Heracles. Used for serving and representational purposes, the Achilles platter was made from a single thick, cast silver plate, the rim framed with a circle of pearls. The relief scenes were shaped on the upper surface of the platter.

The platter is named after Meleager, the hunter of the wild boar, who is depicted in the medallion of the platter, resting with the trophy after the hunt. Around the rim, other Greek mythological stories can be found. In addition to the story of Paris, who judged Aphrodite to be the most beautiful of the goddesses, there are depictions of famous love stories. The platter, which was both used as a ceremonial dish and probably for serving food, was moulded from thick cast silver plate with a string of pearls around the rim. The relief scenes, like those on the Achilles platter, were formed on the front surface. The wide band between the medallion and rim is filled with engraved acanthus leaves.

The deep basin with a beaded rim, shaped from a single silver sheet and decorated with curved grooves, could hold about 6 litres of water and was used for washing the face, hands and feet. The flutes and grooves are reminiscent of the seashell in which Aphrodite was beautified after her birth, and from which this type of basin takes its ancient name (concha). The medallion is decorated with a wallpaper pattern of hexagonal "honeycomb" motifs. The hexagons are mainly filled with plant motifs, but various vessels, fruit baskets and birds are also seen among them, which suggest the abundance of nature. The washbasin together with the geometric ewers formed a uniform washbasin set.

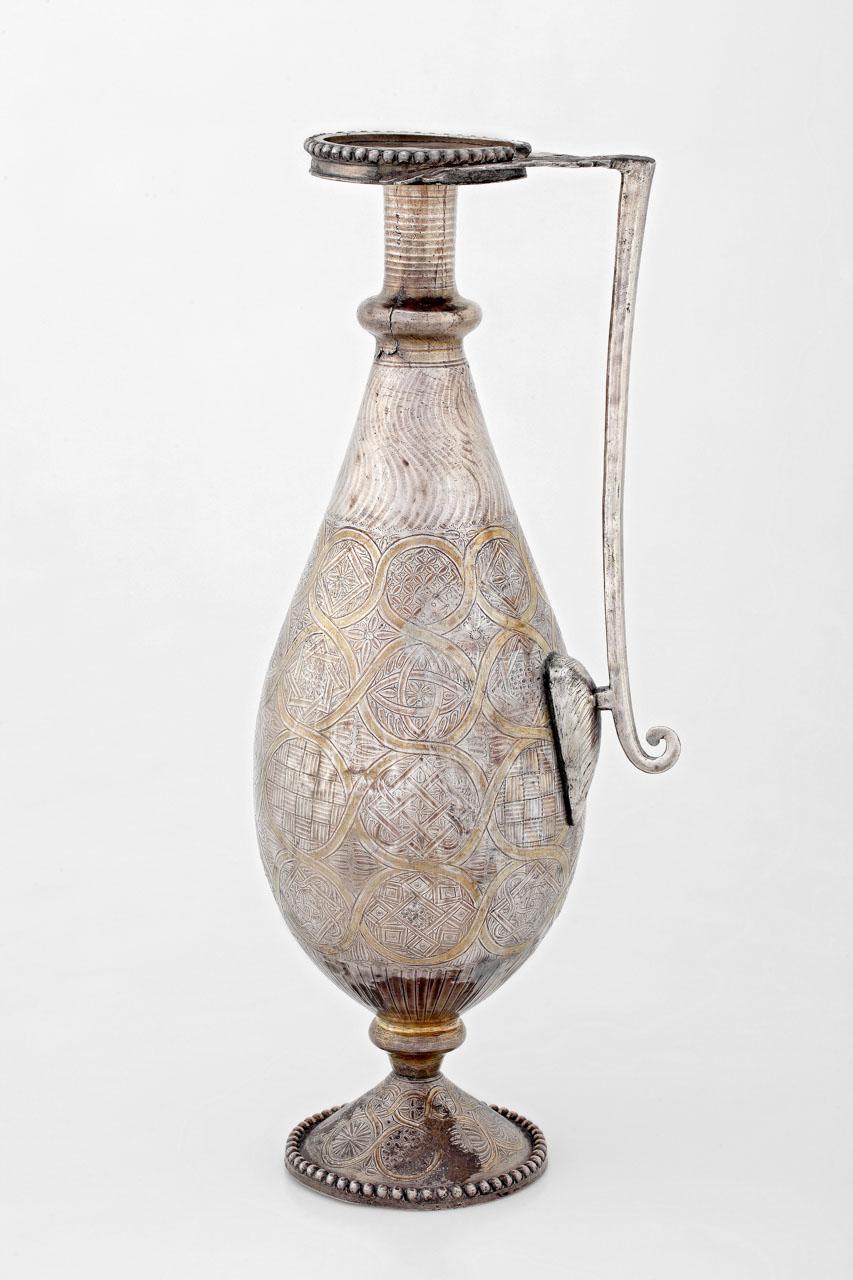

Two ewers of the same size, shape and decoration, with a capacity of about 4 litres are also part of the Seuso treasure. They formed a uniform set together with the washbasin. They were used as water jugs to pour hot and cold water from during daily ablutions or feasts. Originally, both were fitted with a finger rest and a hinged tap lid. The upper part of their handles is decorated with openworked vine motifs and their rims and bases with a string of pearls. Their shoulders are divided by parallel grooves running in a wavy line.

Two ewers of the same size, shape and decoration, with a capacity of about 4 litres are also part of the Seuso treasure. They formed a uniform set together with the washbasin. They were used as water jugs to pour hot and cold water from during daily ablutions or feasts. Originally, both were fitted with a finger rest and a hinged tap lid. The upper part of their handles is decorated with openworked vine motifs and their rims and bases with a string of pearls. Their shoulders are divided by parallel grooves running in a wavy line.

His decoration takes the viewer into the world of amphitheatres. The entire surface of the jar, standing on a decagonal base, with the capacity of about 4 litres, is covered with 120 hexagonal fields. Some of them are decorated with floral motifs, others with animal and human figures. Besides the masterfully engraved lions, boars, bears and hares, figures of bestiarii (young men holding whips) pitting wild animals against each other in the amphitheatres are also seen. The top of the ewer and the hemispherical lid are decorated with male busts and heads. The neck of the vessel is surrounded by a sculptured oak branch with acorns. The animal ewer may have been part of a toilet set, but it could also have been used as a wine jug.

The silver stand at Kőszárhegy is the only surviving late Roman silver stand. It is the highest and the heaviest of any known folding stand. It must have been also the heaviest and therefore the most valuable part of its set. The legs, decorated lengthwise with beadwork, are crowned with sculptural groups of sea centaurs (tritons) and sea nymphs (nereids).