500 years of Reformation

The era of Reformation reshaping Europe began with Martin Luther entering the scene. Values raised by the Reformation belong to Christianism, while heritage of Christianism is universal to the whole mankind: the process that began half thousand years ago still has its effects on our lives.

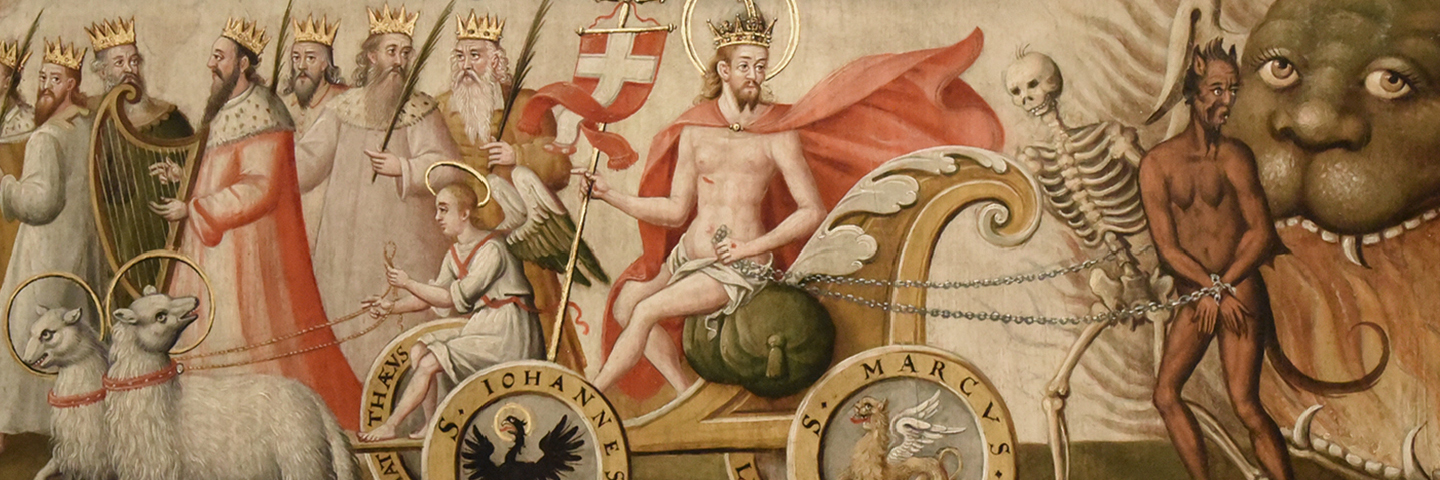

Europe in the 15th century was bursting with anticipation, fear and hope. The plague epidemics – the evil feasting in the world – decimating the secular society and the church alike, the evil feasting in the world made the majority of the Christian community find new ideas to follow. Searching for salvation created forms of piety never seen before and launched new social-spiritual movements. Prophets popped up everywhere preaching about the end of the world closing in, encouraging conversion and purification of the church and declining the practice of paying money instead of acting in the right Christian way.

The theses of Luther made it to Hungary and to the royal court in Buda itseelf as early as the 1520s by merchants, German noblemen and Humanists. Secular and church authorities also acted against believers of the new doctrines, however there were no mass burnings at the stakes in Hungary – unlike in many countries of Europe.

The outcome of Battle of Mohács shocking the religious population praying for the protection of the church and help from the saints was a breakthrough for the new theses reaching more and more people. Believers were longing for an explanation on the failure and comfort in their miserable everday life during the Ottoman occupation. At that time true answers seemed to be coming from the representatives of the revival of Christianism.

Starting from the 1530s preachers had been wandering about in the country mixing new and old in their teachings. Many of them believed that the unity of Christiandom could be restored, however, new frameworks for new churches were clearly forming in the 1540s. Due to the advancement of the Turkish army it was not possible anymore to fill in Catholic Episcopal positions since bishops in the regions in concern could not concentrate on their religious duties only on their political ones. As a consequence new churches coming into life could easily make up for their duties and fill in the old, empty structure.

Noblemen either supported or tolerated these new communities. Even the royal court did not prosecute them in the fear of risking the protection of the country by taking up another conflict with the Protestant nobility. The royal court tacitly accepting these changes made it possible to convert the majority of the population into Protestantism on the ruins of the medieval Hungarian Kingdom – now torn into pieces.

Communities were springing to life all at once in regions of the country controlled by the Catholic Habsburgs or the Turkish and in the Transylvanian province that used to be Catholic for a start, then more focusing on the doctrines of Luther, then Protestant, later Unitarian and finally Catholic again. Uniquely, even the radical ways of Protestantism could be formalized and turned into a more moderate official communion.

The era of Reformation in Hungary had another strong focus: people had to realize and digest the Turkish occupation and the encounter with a shockingly different culture. People at the individual and also at the community level had to confront with the feelings of mortality and unpredictability and accept them as parts of their daily lives. Everyone was devoted in looking for the causes of the country and nation falling apart and the possible ways of surviving and restarting then buliding up a new country.

During its history Hungary had always been ethnically diverse and its people had always been following several religions. By the second half of the 16th century the country was lost in the political sense due to the Turkish occupancy and being torn into three parts. The permanent and threating presence of the Turkish power, the cooperation they forced with Hungarians in the occupied regions and the power vacuum all led to an unprecedented level of freedom of speech and religion resulting in the Carpathian Basin turning into the most diverse parts of Europe in terms of denominations. Most of its counties and regions did not remain untouched nor in unity.

An important condition for Reformation taking place in the 16th century to survive and for the new-born communions staying sustainable for a long period was that all stakeholders trying to amend the posititon of the country engaged in discussions with each other in spite of their political or religious differences. This way they all clearly made a statement for the service of the homeland even if their tools and measures were different. Seemingly unproductive discussions and verbal fights proved not to be useless at all in the end as they helped to give birth to a new type of community identity and taught people and communities how to adapt themselves to living with others thinking in a completely dissident way.

Disparities between Protestants and Catholics, between freedom fighters („Kuruc”) and their opponents („Labanc”) did no disappear with time. However, their constant rivalries helped to shape the image of new the Hungary in modern times. Eventually Reformation proved to be a process giving place to a modern, self-reflecting mentality taking responsibility for itself and its environment.

Grammar and Grace is an exhibition of the Hungarian National Museum offering the visitor to take a look at the ever-changing, complex relations of the Hungarian Reformation, to discover unequalled treasures and to be informed with the help of detailed explanations. Portraits of Transylvanian princes, the only existing copy of Gál Huszár’s hymn-book, select items from the Esterházy Collection, political handouts from the 17th century and the 18th century organ of Torvaj all represent the mental and physical notes made by the Reformation in the last five hundred years. This exhibition was brought to the audience by the exemplary collaboration of museums, collections and parishes in and out of Hungary.

Curators:

dr. Erika Kiss (Hungarian National Museum)

dr. Botond Gáborjáni Szabó (Museum of the Reformed College of Debrecen)

dr. Zsuzsa Fogarasi (Ráday Museum of the Reformed Church Diocese of Dunamellék)

dr. Béla László Harmati (Lutheran Museum), dr. Botond Kertész (Lutheran Museum)

Zsuzsa Zászkaliczky (Lutheran Museum)

Márton Zászkaliczky (MTA BTK Institute for Literary Studies of Hungarian Academy of Sciences)

Dr. János Heltai (National Széchényi Library)

Design: Tibor Somlai

A studio exhibition titled Protestant ways of life in the 20th century is connected to Grammar and Grace organised by Gyula Hosszú. The exhibition houses ReFilm – Week of Protestant Documentaries from 2 to 7 May 2017.

Sponsors:

Reformation 500 Committee

Ministry of Human Capacities

National Széchényi Library