A clock is not only a timekeeping device, but also a feast for the eyes, collecting clocks has long been a pastime of the aristocracy. The first inventory book of the Hungarian National Museum, the Cimeliotheca, already lists several "horologia" among its artworks in 1825. Some very significant pieces were added to the museum in the 1830s with the Jankovich collection (including the clock of Prince Zsigmond Báthory of Transylvania) and the Delhaes collection (1902), and over time, numerous clocks associated with historical figures have also been added to the collection. The separate Collection of Clocks and Instruments was established during the reorganization that took place in the 1950s.

Contact: Dr. Klára Radnóti, radnoti.klara@hnm.hu phone: +36 1 327 7716

Composition of the collection

The collection includes various types of sundials, including compendiums (complex instruments) and astrolabes, instruments used for mapping mines (only two, but these are unique pieces that show that Hungary was at the forefront of mining and the mechanaical industry necessary for it in the 16th century), and mechanical clocks (wall, table, furniture, and portable clocks). A few other items are also present among them that do not belong elsewhere, such as the equipment of a turn-of-the-century photo studio and an astronomical telescope from the early 19th century.

One of the earliest pieces in our collection is this clock with a gilded copper frame, which, according to tradition, once belonged to prince Ferenc Rákóczi II. In the upper part of the ornate frame, two lions hold a silver oval shield, while on the dial, two warriors battle a three-headed, flame-breathing dragon. The clock is bearing an engraved master's mark: Matthias Kielbich in Pressburg, and in good working order. (Second half of the 17th century, Pressburg)

The crucifix clock used to be a popular type in 16th-17th century Europe. The mechanism is located in the base, which uses a transmission to rotate the sphere with the hour markings on the dial (in this case, Roman numerals) mounted on top of the crucifix evenly along a vertical axis. Time is indicated by a hand fixed in front of the sphere. In the middle of the 19th century, Mihály Nagy, parish priest of Ebed, bequeathed his clock to the National Museum in his will, and it thus became part of the collection. A picture of it was published in a commemorative publication issued on the 100th anniversary of the museum (1902): "On a cleverly composed clock, made in the shape of a crucifix and equipped with a bell, we can read the name of the worthy Hungarian master under the bell..." According to the Latin inscription, it was made by Master Ádám of Bács County in the year of our Lord 1693. (Master's mark: "Me fecit Adamus Bachmedjei A. D. 1693", gilded copper, verge escapement clock)

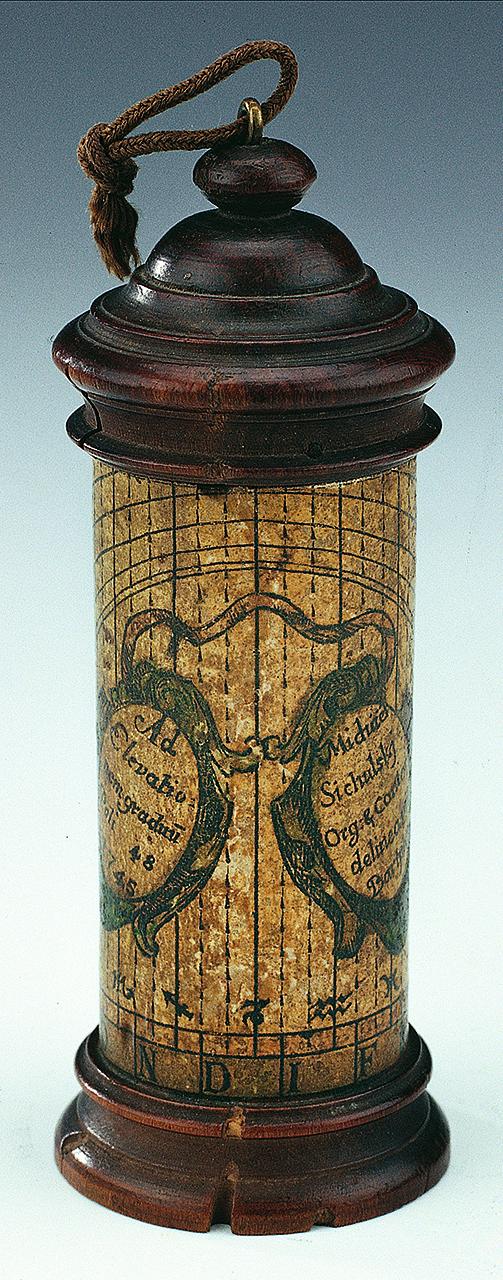

For thousands of years, sundials used to be the most reliable timekeeping devices. Sundial construction, gnomonics (a gnomon is a shadow-casting stick with a circle drawn around it, so that the position of the Sun could be determined from the changes in its shadow) became a science in ancient Greece. Sundials can be divided into two main groups: fixed and portable devices, with many different subtypes within each group. Portable sundials became more widespread in the 15th century, when there was a growing need for more accurate timekeeping devices in everyday life. Pocket sundials flourished in the 18th century, when they replaced the much more expensive mechanical watches. The cylinder sundial is based on measuring the altitude of the Sun. The dial is on the cylinder's mantle, and the horizontal gnomon at the top casts a shadow on it. This is a remarkable sundial that also measures quarter hours. According to its Latin inscription, it was "drawn by Mihály Sichulsky, organist and cantor in Bártfa (today Bardejov, Slovakia), at a polar altitude of 48 degrees, in 1745. (Marked: Michael Sichulsky, Bártfa, 1745.)

This finely crafted gilded copper disc is an outstanding piece in the Hungarian National Museum's collection of clocks: an astrolabe combined with a nocturnalium. The astrolabe is used to determine the orbit and current position of the planets. It is a model of the Ptolemaic universe and was the most widely used scientific astronomical instrument in the European Middle Ages and Renaissance, serving as an observation and calculation device suitable for many types of measurements. It is fixed on a circular base plate (the mater), which has angle and hour markings on the rim. One (or more) angle-marked discs, tympani, can be fitted to the front of the base plate – these were engraved with a flat projection of the celestial sphere's grid. The zodiac ring shows the the zodiac scale, with the names of the constellations. Above this is the rotating star ring, the rete. The rete contains 28 spikes marking bright stars. The layout of this instrument differs somewhat from the general system of astrolabes. The back side is a complex star clock (nocturnalium) – unfortunately deficient. There are two rotating discs on the back, but the star clock's hand is missing. It is decorated with an engraved drawing of Aries. The engraved Latin names also indicate that the instrument was made before the 17th century. It is an interesting and unique piece. (No maker's mark, South German or Flemish work, 16th century, gilded copper)